An actor friend called Matthew Scurfield was a member of the repertory theatre company in Barrow-in-Furness. At one point in the play, which was a period piece, he was required to march on stage, stand before an expectant throng of actors and deliver a mighty and important speech. Matthew strode to his final position, stood with his back to the audience and gathered his cape around him. He then drew himself up majestically and extended his arms wide, holding on to the wings of the cape. He was bollock naked. Thus disarrayed he delivered the entire speech. The actors could not possibly be seen to react. He could have killed somebody.

In 1982, towards the end of a performance of ‘Circus Lumiere’, Lumiere & Son’s most popular show, the five male performers, at the behest of Pamela the Ringmistress, enter the ring in their underpants in order to reenact their days as wild men in the jungles of Brazil. The uncouthness that they displayed before their discovery by Pamela, who had civilised them then launched them as circus performers, was made evident in the way they fought incessantly among themselves. This flashback sequence was punctuated by snap blackouts, during which the performers would assume fresh tableaux comprising complicated interlocking stacks of grappling bodies. For the effect to work properly, the audience must not see the performers changing position and the performers must move at top speed in the dark in order to be discovered ‘magically’ reassembled when the lights snap back on. On one occasion I hastened to my next position – a manoeuvre that had been rehearsed many times – and sensed that I was a tiny bit late. I dived into the pile of bodies just as the lights came up. I found that I was sitting on George Yiasoumi’s face. There then ensued a bout of uncontrollable behaviour that will be the subject of this post.

Similar behaviour can be easily located in such arcana as any Jim Carrey Blooper compilation on YouTube. His ‘Liar Liar’ bloopers will be found instructive in this respect. In the footage Carrey is seen pursuing two slightly different paths. Characteristically working at a maniacally elevated pitch he displays an impatience to achieve the results that the overall film project is designed to deliver. Some of the bloopers are simple errors based on bumping into the scenery or getting the lines wrong and they precipitate fits of giggling in all the actors present in the scene.

In these situations Carrey is rarely content simply to fail. He picks up on his initial mistake and runs it through a few more gears before giving up in order that a fresh take may be taken. He will land on a rather small error, which could easily be ignored, and instantly extend it, as if the end result of the extension represented the real nature of the original mistake. His fellow actors usually crack up and, as a result, perhaps Carrey gets a preview of the effectiveness of his comic persona. If this is the case then what the other actors and crew give the star is not an endorsement of the work in progress but an acknowledgment of the tension generated by that work. The cracking up demonstrates that the actors are tense and are pleased to experience relief from that tension. That they are tense simply indicates that they are professionals – they wish to optimise the presentation of their skills come what may and their attention is monopolised by acts of concentration, memorisation, collaboration and, importantly, surrender to the qualities of the character they are portraying. Carrey is also often seen – at least in the blooper reels – to subvert/ undermine/increase tension (possibly constructively) and show off as he deliberately strays off script to deliver gags and pull faces that make him and most of his colleagues snort explosively or bray with delight. It’s debatable who is the more tense and therefore has a greater need for the release, Carrey or those working with him.

Carrey, in other words, enjoys corpsing and making others corpse. The term derives, it is thought, from the mischievous practice of trying to make a corpse, to be precise an actor playing a corpse, laugh when they should not even be seen to breathe. The risk here would be that corpsing is very contagious and may well reduce the least hardy of the company to helpless giggles as well. From the corpse’s point of view, then, the ideal position in which to play dead would be one in which you are facing upstage, away from the audience.

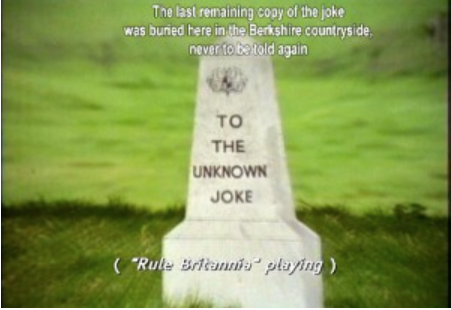

Corpsing is odd. It is a forbidden delight, with which audiences eagerly connive. Up to a point. Beyond that point it suddenly looks too easy. The corpsing actors start to feel uncomfortable, despite their being enwrapped and entrapped in the greatest of comforts. The audience suddenly senses that, as far as they are concerned, a few seconds of abandon is quite sufficient. They’d like to get back to the script now please. But why did they succumb in the first place? You pay a lot of money to go to the theatre, why would you be so delighted by the abrupt and thoroughly disenchanting collapse of the whole point of the evening out? Or, why would you appreciate the inclusion of blooper outtakes on your box sets? Why do TV shows based solely on collections of bloopers draw dependably respectable figures? It has been observed elsewhere in this publication that actors demonstrate to non-actors that it is possible to act. This disclosure can be taken as an endorsement of the practice of pretending – when the occasion seems to demand it – to be other than you are. It can also support the more offensive notion that all behaviour is performance.

Corpsing is odd. It is a forbidden delight, with which audiences eagerly connive. Up to a point. Beyond that point it suddenly looks too easy. The corpsing actors start to feel uncomfortable, despite their being enwrapped and entrapped in the greatest of comforts. The audience suddenly senses that, as far as they are concerned, a few seconds of abandon is quite sufficient. They’d like to get back to the script now please. But why did they succumb in the first place? You pay a lot of money to go to the theatre, why would you be so delighted by the abrupt and thoroughly disenchanting collapse of the whole point of the evening out? Or, why would you appreciate the inclusion of blooper outtakes on your box sets? Why do TV shows based solely on collections of bloopers draw dependably respectable figures? It has been observed elsewhere in this publication that actors demonstrate to non-actors that it is possible to act. This disclosure can be taken as an endorsement of the practice of pretending – when the occasion seems to demand it – to be other than you are. It can also support the more offensive notion that all behaviour is performance.

Whether this makes actual actors seem more or less skilled is open to question. It is, nevertheless, salutary to witness actors at work, especially since most of the time we are sufficiently seduced by the performance willingly to sideline the obtrusive sense that it is a performance. In other words, performances can be credible. And this is good to know. The other side of the coin would feature uneasiness about the whole performance enterprise. If theatre or film performance and everyday performance are comparable in some way then non-actors could be prey to breaks in continuity on a par with those suffered by thespians. Professional corpsing is clearly a breakdown of some sort and may be seen as having its equivalent in everyday social life. Some non-actors can act, in everyday life, better than other non-actors but both parties will experience occasions when they turn in a bad performance. For many this will not be an issue. It happens – move on. However, both professionals and non-actors carry within them the possibility of the flawed and therefore detectable and therefore non-credible performance. While non-actors do not corpse – their performance errors tend not to occur in front of large, attentive and formally arranged audiences or highly focused groups of fellow actors and technical crews – they will regard corpsing as significant rather than trivial. Having suggested above that it is reassuring to know that the act of everyday acting may produce credible (if not authentic) behaviour, the more sweeping suggestion – that all behaviour is performance – may precipitate considerable anxiety.

The laughter business is fraught with danger. Almost by definition laughter is out of control and intense laughter threatens to lead us to a point from which we might have difficulty returning. I’m not suggesting that this is what anyone thinks when they burst out laughing but our colloquialisms do suggest that laughter is not simply restricted to things that we find humorous. I wrote recently about delirious, frightened or horrified laughter in the post ‘Murder in the Dark’. Given that we’re not going to die laughing there still remains within the corpse and the snort more than wholesome, disruptive fun.

The processes that comprise an actor’s preparation do not explain satisfactorily what it is that actors actually do. Somehow they create space within themselves for characters other than their own – that’s pretty clear. One wonders what happens to the actor’s own character when they submit to one that has been constructed in the rehearsal process. In the case of demonic possession the subject is held to be eclipsed or erased by the immigrant evil spirit. The rehearsal process demedievalises this setup, transforming a spectacular event into a series of measured operations.

Romantic misconceptions about method acting not only serve to assure audiences of the authenticity of performances but encourage the idea that the actor dies nightly and is resurrected within the terms of the script. It’s easy to form the impression that accomplished actors move beyond impersonation to almost complete submission to character.

If submission were complete then the actor wouldn’t exist, she would walk offstage, get a National Insurance number and look for something to do with her life. If submission were complete then the actor – like the stereotypical schizophrenic who thinks he’s Napoleon and is disappointed at the lack of respect he receives – would not be able to follow the script, so diverted would he be by the myriad possibilities of interaction with those around him whom he would assume are real people. Notwithstanding the purportedly awe inspiring capacity of some film actors to maintain character between takes, the idea that they forget who they are and only remember the character is silly. They need who they are because so much of what they do on stage or before the camera is technical. They need to stand in prescribed places most of the time and they need to know when the other person’s speech ends so that they don’t interrupt them when they respond. Etc. So this whole submission thing is just not a useful idea. They just submit a bit. Some more than others.

Even so, we are used to thinking that the better they are, the more they have submitted. Perhaps the notion of absorption is more versatile – it could describe a state in which both technical and character requirements are simultaneously maintained in focus. This makes the job sound more difficult yet it does suggest a multi-tasking the components of which are at odds with each other and could not confidently be described as complementary. And this in turn is consistent with a precariousness in which the actor’s condition is vulnerable to breaking down, splitting apart and being defined by neither of its disengaged parts. Suddenly, just because the on-stage drawing room doorknob comes off in your hand, you are between worlds and discombobulated, a zombie with a body but no character.

But they recover. In rehearsal they recover every few minutes. When the director says “Can we stop there for a moment?” the actors jump off the bus, hang around in the bus station with the director then just jump straight back on the bus when everyone is ready. The building of character is an act of composition and the actor is required to hold the character in a state of composure but this can be relinquished when it is appropriate to do so. However, when it is knocked off balance without warning then decomposition can follow, rather than the straightforward on and off the bus that is typical of rehearsal. The world of the actor in a scripted play is both thoroughly stable and teetering at the point of imbalance.

In his remarkable book ‘Boo! Culture, Experience and the Startle Reflex’, Ronald C. Simons presents a detailed study of the latah phenomenon. In Malaysia and Indonesia there are individuals who react to a sudden noise far more violently than others. Simons explains that ‘Latahs do everything that hyperstartling people do elsewhere. They may strike out at objects or others, assume overlearned defensive postures, or say improper or idiosyncratically stereotyped things…The disruption of ongoing attentional processes is for them more extreme. After a series of startles, a latah‘s speech and behaviour may become quite disorganised. In addition, after being startled some latahs experience strong attention-capture, focusing on salient aspects of their perceptual fields and narrowing and locking attention on them. Latahs may call out the names of what they see or repeat or approximate sounds they have just heard. They may match movements of objects or other persons with movements of their own bodies. As with persons whose attention has been captured generally, latahs will sometimes obey imperiously given commands.’

In his remarkable book ‘Boo! Culture, Experience and the Startle Reflex’, Ronald C. Simons presents a detailed study of the latah phenomenon. In Malaysia and Indonesia there are individuals who react to a sudden noise far more violently than others. Simons explains that ‘Latahs do everything that hyperstartling people do elsewhere. They may strike out at objects or others, assume overlearned defensive postures, or say improper or idiosyncratically stereotyped things…The disruption of ongoing attentional processes is for them more extreme. After a series of startles, a latah‘s speech and behaviour may become quite disorganised. In addition, after being startled some latahs experience strong attention-capture, focusing on salient aspects of their perceptual fields and narrowing and locking attention on them. Latahs may call out the names of what they see or repeat or approximate sounds they have just heard. They may match movements of objects or other persons with movements of their own bodies. As with persons whose attention has been captured generally, latahs will sometimes obey imperiously given commands.’ Latahs or their non-Malaysian and Indonesian equivalents are found in many societies. They may not have the special status afforded them in these regions but the precariousness of their composure is much the same. They will ‘jump out of their skin’ and not be able to get back where they belong for minutes at a time. During this time their capacity to direct their own behaviour is spectacularly diminished to the point where they will be compulsively obedient or repetitive. They are, in a sense, ‘anybody’s’. While corpsing actors cannot be described in these florid terms, there is a similarity in the abruptness of the shift from composure to disarray in both latah and corpsing actor. Actors may be, in the particular sense I have suggested, fragile, but only when they are acting. In the case of the latah it is as if their entire being, or their sense of being, will only cohere if they are never startled.

The video clip demonstrates that the non-latah peers of the latah individual tend to tease the latah, sometimes mercilessly, in order to precipitate what is clearly regarded as an hilarious performance, available on demand and unticketed.

Now let’s look at Andrea…

¶¶¶¶¶¶