Around here real and imaginary characters are shockingly always crossing paths.

Diane Williams – ‘How Much Did You Ever Think the World of Me? (2019)

The mammals of the Oligocene are often described as though they were halfway creatures, semi-formed prototypes: dog-bears (bear relatives that looked like dogs), bear-dogs (dog relatives that looked like bears), large cat-like sabre-toothed hunters that were not true cats, and the most charismatic members of the Oligocene bestiary, the entelodonts, or ‘hell pigs’: each as big as a cow and equipped with huge crocodile-like jaws, a sort of ‘gigantic, hyper-carnivorous warthog’. Not actually pigs at all, they were more closely related to whales.

Francis Gooding – ‘Hell Pigs’, a review of Tim Flannery – ‘Europe: the First One Hundred Million Years’, London Review of Books vol 42, #1. (2020)

Among the many inhibitions that beset my writing for performance there is, in addition to a number of quite severe constraints that I apply voluntarily, one that never relaxes its grip and must be regularly challenged. It has an almost irresistible force and settles on me like a slothful powdery moth coiling and uncoiling its proboscis, injecting a nectar that tames unruliness and blankets the mind with logic. Narrative has a uniquely sedative gravitational pull that, I find, scuppers the poetic pleasures of disconnection and incongruity. Write half a page and groan, even as you strike the keys, as beginnings sprout middles and middles taper to their ends.

It’s hardly a novel thought (it’s hardly a novel) but if you don’t want theatre to tell stories then there are countless alternatives to narrative structure. The first performance script I wrote was ‘Jack, the Flames!’ (1972) and it was significantly lacking in throughlines, coherent structure and character depth. Which is what I wanted. I was in the habit of writing down my dreams back then so I transcribed some of them then imitated them to generate more text. The script was all over the place but Hilary knocked it into shape. For the next few years, however, with subsequent shows, I was bothered by the feeling that maybe I should pay more attention to this structure thing. I tried to put endings on the scripts that felt like endings but they were the weakest part of these works. I was very taken with The People Show back then and they never had endings. Or proper beginnings really. But when I picked up my pen (there were no PCs then) I couldn’t stop drifting into narrative. I’d go for a few pages without it and the next thing I knew I was connecting up the scenes as if they were going somewhere. I just couldn’t stop it.

I found myself doing something I didn’t believe in but it would creep up on me. It wasn’t that I wanted to be a proper playwright, I’d never wanted that. I liked other people’s stories in films and books, no problem there, but I didn’t find their various structures appropriate for theatre. I didn’t actually find theatre’s own structures appropriate, come to that. But when I was about 18 I read Ulysses in my bedroom one summer and that did it. A little while later I read Naked Lunch. After those two books there was no going back. I mean, do you want to live forever in your home town? Between about 1962 and 1972 I was gratifyingly overwhelmed by a barrage of experimental films, novels, poetry and Happenings and moved in circles increasingly populated by adventurers presenting a variety of pathological behaviours. All this was both formative and obliterative. I had so decisively crossed the channel that I couldn’t have gone back if I’d wanted to. To aspire to narrative would have been a betrayal of all that magnificent reading and viewing and hanging out.

But although I felt I had placed myself beyond the allure of the conventional play form, I hadn’t reckoned with the after effects of the 18 years of exposure to narrative that had preceded the meltdown. My parents were not connoisseurs of the arts but in their bookshelves I had discovered and devoured Steinbeck, James Jones, Salinger and Huxley. Throughout my boyhood I had returned time and time again to my father’s collection of Richmal Crompton’s William books and loved every single page of the witty, eventful, stories and their variously naughty, irascible, pompous and vain characters. In all this pre-adult reading I was gripped by the expressive elements on display, including the construction of narratives. But a few years later, the early 60s tsunami kicked in, I read Artaud at university (as distinct from the Eng Lit for which I had enrolled) and thought that I was ready to dance my own steps.

I saw four or five films a week at Uni, in the local cinemas, the local art-house cinema and the Uni film societies. After Uni I went to film school. I had already seen Breathless (1960), Zazie dans le Metro (1960) and Jules et Jim (1962) in my home town and along with my fellow RCA students I then revelled in a three year binge during which it seemed that a new Nouvelle Vague film, or something European with a similar spirit, was being released every week.

It was the thing in my home town to shout out in the cinema. Wags of all classes would bellow witty, indignant, inspired, vocal graffiti at the screen, usually to roars of approval and, in the case of those cinemas with raked floors, the rolling of empty bottles downhill towards the screen. There are many such outgusts that I cherish to this day, among them ‘Shag’er while she’s still warm, mate!’ addressed to the monster hovering above the body of the scantily clad young woman he had just killed; also ‘What about the woodpeckers?’, a riposte to Rod Taylor, in ‘The Birds’ (1963), who has just frantically nailed boards across all the windows and doors in the house under attack by angry birds in order to save Tippi Hedren and himself and then mops his brow and says to Tippi ‘We should be all right now.’

Quite why Roger Dibbs undertook to come to a showing of Alain Resnais’ ‘Last Year in Marienbad’ (1961) I’ll never know. One of the artiest art-house films in the world at that time, it had done well at the Venice International Film festival but had, as they say, divided the critics. On one side of the critical chasm were those found it hopelessly obscure, painfully slow, devoid of meaning, little more than a form of torture. Others considered it to be a thing of great beauty, a masterpiece, ‘one of the most influential movies ever made (as well as one of the most reviled), Marienbad is both utterly lucid and provocatively opaque’ (J. Hoberman, Village Voice, 2008).

Roger Dibbs was a very cool dancer who was into jazz rather than The Beatles. He was well groomed in a tasteful European jacket and tie style, something of the lounge lizard about him, and his skills included the throwing of window boxes full of soil and flowers through the plate glass windows of the Lending Library, setting fire to a great pile of old newspapers in my friend’s mother’s hallway and tipping a huge ornamental urn from a pub balustrade onto a white Triumph TR4 sports car parked ten feet below. The police hurried to the last scene and captured half a dozen of us. Dibbs vanished but we resolved the issue by saying to the main policeman ‘Roger Dibbs did it and this is his address.’ He was a vandal, but so well dressed. I call his vandalisms skills because he practised them often, usually at the weekends, and they acquired greater and greater polish as he moved with charm and reserve through the leisure circles of that town in a flat area of the country.

Anyway, after about 25 minutes of vitalisingly melancholy monotone French voiceover as the camera tracked ‘once again, down these corridors, through these halls, these galleries, in this structure of another century, this enormous, luxurious, baroque, lugubrious hotel, where corridors succeed endless corridors – silent deserted corridors overloaded with a dim, cold ornamentation of woodwork, stucco, moldings, marble, black mirrors, dark paintings, columns, heavy hangings, sculptured door frames, series of doorways, galleries, transverse corridors that open in turn on empty salons, rooms overloaded with an ornamentation from another century, silent halls … ‘ there erupted across what, up to that point, had been a poised, unbreathing silence a stentorian interruption from the cheap seats. Dibbs – ‘It’s a load of bollocks, isn’t it, Dave?’

Delighted as I was with his uncouth observation, I didn’t actually agree with Dibbs. I felt his pain but also my own shocked enchantment. I have held Marienbad in my top three for some considerable time and while my own shows are considerably faster paced and regularly feature spasmic, homicidal and tourettish outblasts, the languid, plotless, frozen, dreamy world conjured by Resnais and his screenwriter Robbe-Grillet, with its barely mobile, stately and expressionless actors speaking without emotion or facial nuance is just what the doctor ordered insofar as I find it unfailingly restorative and just plain exciting. Lynch produces similar effects but they, like Fukunaga and Pizzolatto’s ‘True Detective’ (2014) and Refn’s ‘Too Old to Die Young’ (2019), are enhanced by explosive scenes of violence and episodes of manic pace. Refn actually out-slows Resnais – his 13 hour, 10 episode TV show glaciates exquisitely, pushing the envelope off the edge of the escritoire with the ‘Is there something wrong with my TV?’ majesty of the dialogue scenes – every single one of the dialogue scenes – in which characters routinely pause for between three and five seconds between exchanges – to call it a tic makes it sound screwball, it’s a cavernous tock – without ever acknowledging any situational reason for this extreme stylisation. The effect, in all three cases, is to bathe the most routine scenes in unremitting dread.

I took most of my cues from films. But in 1963 or so I was mightily impressed by Artaud’s short play ‘A Spurt of Blood’ (1925), whose preposterous, deranged, mythopsychoanalytical delirium I experienced as a soothing balm. I directed a version of it while at film school. The skies rained offal.

It helped that I didn’t like theatre itself very much. It was basically very strange but everyone behaved as though it were perfectly normal to carry on like that. The utter oddness of dressing up, learning lines, pretending to be someone else and inhabiting a space bounded by flats, drapes and lights was rarely acknowledged. This awkward other-worldliness was compounded by, in this country at least, the deployment of a range of hystericised (but not invigorating) speaking styles which, at their particular times, were held to be in some way reflective of the way people spoke and thought in the nearby everyday life.

Theatre was clearly stuck and it annoyed me. When I went to see it by accident it made me bad-tempered. But there was so much to be taken from films and books.

A few months ago, idly, from the top of a bus, gazing at nothing much, noticing a large municipal Christmas tree decked with white lights. A person with a dog is pushing at the tree making it undulate. Why would they do that? The picture clears: it’s not the person that is undulating the tree, it’s the wind blowing across it. The person’s arm is extended towards the tree, yes, but they are not touching it. I forgive the person. The event fades and becomes nothing. A slip of the eye. The essence of a disposable event. To call it the essence of anything is to grant it an undue importance. This kind of thing goes on all day long. It deserves to be edited out. Deleted. Surely even a human mind, which seems to be able to hold an infinite amount of information, need not process this kind of flotsam. Just let it pass. The alternative is to remember too much. To be cluttered as a matter of course.

Or just today, a bespectacled red-faced man walks past the window. He has a monstrous extra face beneath his chin. It ripples down to his top shirt button. Well, for a second perhaps. The kind of thing that happens when you’re wearing your reading glasses rather than your street glasses. It’s just a glasses thing. Gone with the wind. No big deal. But in that second what a show! A flesh riot in the high street!

Where do these snippettes come from? Do we make them up on the hoof, effortlessly, like nonchalant poets? Are our skills in this regard so fluent that at the least suggestion of an interruption to the flow we activate an elusive but super-efficient mechanism that seals all gaps? Which in turn suggests a certain urgency. What’s the rush? What could go wrong?

It would be a mechanism that works on an anything-is-better-than-nothing principle: if we didn’t fill those gaps, who knows what would press forth? But in the case of the extra face, monstrosity emerged anyway. And isn’t that something we’d rather not know about? So maybe ‘making them up on the hoof’ isn’t the way to look at it.

In fact it’s as if ‘we’ have very little to do with it. We just provide a platform. The images pop up in one piece, ready to go. A bit like an encounter with the Australian stonefish which delivers an incapacitating sting when accidentally stepped upon in shallow seas. We just do the treading – we didn’t ask for the fish.

It is unlikely that there is within us a repository in which resides, say, an image of a monstrous extra face suitable for insertion beneath a passerby’s chin. There is, however, the silent continent, the inland empire, the unconscious which is by its very nature restlessly protean. So utterly efficient is the messaging connectivity that, in terms of filling the gaps, it’s like lying in a tent in the rain – an incessant drumming against a membrane that keeps us dry but if you poke at it the water gets through. Is it conceivable that the rain is always raining? And the only reason we are not constantly drowned by intrusions is because we keep busy?

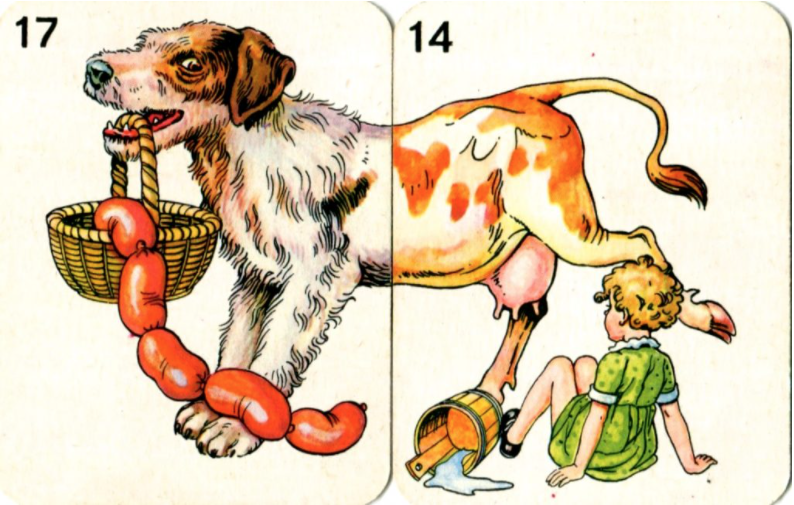

Were there such a repository then this is how its contents might be stored

The other weekend The Guardian had a story about Haribo suing some Spanish bar owners who were selling jelly bears containing alcohol. The Spaniards, the report said, ‘planned to carry on selling their products in Spain – and to their customers in France and the UK – to show that their bears would not be cowed.’ This raises the question of whether Haribo has a position on cows that will not be borne.

I realise this is not top notch wordplay but it had to be done. Ideally the past participle of ‘bear’ will not be ‘borne’, it will be ‘beared’. This would then deliver the much desired ‘cows that would not be beared’. This, in turn, suggests that the cow will resist transformation into a feared rather than domestic creature.

On the other hand, in the statement ‘Peter and Susan were cowed by dogs’, we will find, lightly concealed, the possibility that ‘Peter and Susan were dogged by cows.’ So much better. It suggests that, under certain conditions, the placid cow will be caninised.

It may seem odd, decadent even, to dwell on such fleeting flukes. To treat them as if they had something to say. It must be said, however, that, in their way, they do approach the Oligocene. (See quote at top of post.) In the Oligocene (I keep writing it ‘Oligoscene’ so I looked up ‘oligo’ just now and what do you know: just a few or scanty. From the Greek ‘oligos‘ (as in oligarchy but I was slow to make the connection) (palaeontologically speaking it must refer to an era of which little is known) (despite the profusion of creatures for which it is known) it is clear that things were coming and going, crossing paths, colliding, blending, unblending, indecisive, changeable, making up their minds, haven’t quite got this but we’re getting there, this will never work, it could go either way, yeah but give it a chance

I was driving along the M4 out of town one time and had to slow down because of a collision up ahead. As we crawled past the police cars a bizarre sight slowly came into view. On the other side of the buckled crash barrier two trucks had clipped each other with such force that their rear doors had burst and their contents were strewn across all six lanes of the motorway. The drivers were talking to the police on the hard shoulder. One truck had been full of furniture – sofas, armchairs and tables. These were lying randomly around on the tarmac. The other truck was a baker’s truck and had been full of loaves, buns, tarts, doughnuts, battenberg slices, cupcakes and bags of flour. The bags had exploded and created a Christmas scene across ground zero. A heavily powdered sofa bore several dainties in odd clusters and ragged stacks, as if impulsively abandoned by two untidy people. Slices of white bread festooned an inverted reclining chair. Jam doughnuts littered the scene like beached anemones. And so on.

As well as resembling a respectable site specific installation piece, the spectacle was a fine snapshot of the poetic process which went some way beyond ‘the chance meeting on a dissecting-table of a sewing-machine and an umbrella’ to a higher hybridism wherein the battenberg on the scatter cushion was not on it but of it. A creature of a drained undersea world.

the possibility of recognising nature, even distorted nature, which is, after all, a kind of struggle between my interior life and the external world as it exists for most people

Picasso in ‘Life with Picasso’, Francoise Gilot (1964)

Freud, of course, gave us the Slip (in ‘The Psychopathologies of Everyday Life’ (1901)), something of an ur-text here insofar as it introduces the notion of the unbidden utterance – an involuntary speech event featuring the partial expression of unsettling memories and ideas in words which resemble and replace those that would have been spoken as part of an uncorrupted original remark. A similar but visually based principle animates what we could call the space-filler, wherein an often minor, often everyday, occurrence seems to elude comprehension yet is nevertheless, with the speed of thought, framed within an interpretation. The malfunctioning aspect of this operation – the absence of an initially acceptable understanding – features the barely conscious acknowledgement of a gap, a black hole, in the generally unstanchable stream of consciousness. Nature adores such a vacuum. Ever loaded, always cocked, it will spritz the narrative with alternatives drawn from what is probably a vast but uncatalogued collection of all that is inconvenient. A malcontent is undulating a tree. Public order is breaking down. A public good is being trashed.

(An earlier version of the paragraph above referred to ‘unnatural alternatives’ ( 2 lines from end of para) – this is careless. It suggests that the natural is limited to what we know. ) (Picasso saw it otherwise: “…I don’t want there to be three or four or a thousand possibilities of interpreting my canvas. I want there to be only one and in that one, to some extent, the possiblity of recognising nature, even distorted nature, which is, after all, a kind of struggle between my interior life and the external world as it exists for most people….I don’t try to express nature; rather, as the Chinese put it, to work like nature.”)

Reading an article on ‘Little Women’ (2019) in Sight & Sound (January 2020) I glanced at one of the accompanying photos and was surprised to note that Emma Watson had folded her right leg across Greta Gerwig’s lap as she studied the script with the director and cast members Saoirse Ronan and Florence Pugh. Watson is slight of build yet her bent leg looks quite heavy. Her posture also looks quite uncomfortable.

But, of course, Watson is doing none of this. The ‘knee’ that is seen is formed by the lid of Gerwig’s laptop and her ‘calf’ is Gerwig’s lower leg. The photo is sufficiently dark to allow the casual glancer to fuse the two dark objects into one encircling limb. If the exposure and contrast are tweaked with photo editing tools the actuality of the arrangement becomes crystal clear:

In such a situation if one would be asked ‘Are you seeing things?’ then the answer must be ‘Yes, I am.’ And supposing it were then asked ‘These things that you see – are they worthy of remark?’ then the response should be frank: ‘They are largely useless. Most would be wise to ignore them. There may be those who have some use for them, however.’

It took several minutes to write the three preceding paragraphs and less than one half of one second to misread the seating arrangements in the photograph. Correction of that misreading took perhaps three or four seconds. The economics of this are sufficient to dispel any ideas of the value of the mistake that can never be made again. But I dwell on such phenomena in part because they are so hastily discharged.

These corrections and realignments probably happen throughout everyone’s day every day on the planet all the time. They probably start when everyone is very young, when a mixture of misreading and intermittent realignment is all we have. A little later realignment becomes a more conscious operation as our confidence feeds off a steadily expanding bank of successful adjustments. And of course, as we get older it is as if the need for realignments is greatly reduced, our skills in this field are consolidated and the incidents, if they are noticed at all, have no more importance than an itchy nose. It may be, however, that it’s not so much a matter of skill as we simply learn to ignore events that have no apparent meaning or value.

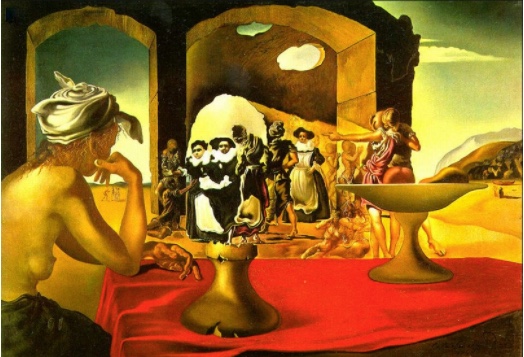

In order to resurrect then reinstate a capacity for misperception, Salvador Dali conceived the Paranoiac Critical Method, wherein a specialised personal effort was required to undo the habit of ascribing an essential, final reality to objects in the world. By incubating some of what he considered to be the crucial characteristics of a paranoid state of mind he sought to expose himself to the world equipped ‘to systematise confusion and thus to help to discredit the world of reality’ (1930). The world thus apprehended will be constructively contaminated, its objects will be surrealised. Dali would deploy ‘a delirium of interpretation’ informed by ‘irrational knowledge’.

The crucial achievement of one who has deliberately and perhaps ‘methodically’ developed a paranoid frame of mind is to find, with considerable rapidity, connections and associations between objects and ideas that have no association or affinity. This destabilised mode of seeing lends itself equally successfully to the production of the double image, defined by Dali as ‘a representation of an object that is also, without the slightest physical or anatomical change, the representation of another entirely different object, the second representation being equally devoid of any deformation or abnormality betraying arrangement.’

Ernst, in a lecture delivered in 1935, described the objectives of systematic derangement variously: / the exploitation of the fortuitous meeting of two distant realities on an inappropriate plane / (a) means of bewitching reason, taste, and conscious will / the cultivation of the effects of a systematic bewildering / based on nothing other than the intensification of the irritability of the faculties of the mind /

The paranoid state was held to have artistic value (in addition to its capacity for enabling misery and terror) insofar as it, apparently effortlessly, remodelled the exterior in the terms of some of the more volatile or inconstant currents of the unconscious.

When we did peripheral vision in A level Biology we learned some things that were useful. The usefulness of some of these things was immediately apparent and I have valued them ever since. There are various types of gaze. The dominant one is characterised by visual fixation and refers to the field of vision within the point of fixation – the centre of the gaze. Vision beyond the bounds of the point of fixation is deemed peripheral vision and takes up the larger part of the visual field.

One thing in the diagram that fixates attention is the unusual scope of far peripheral vision. You can see behind you. If you look at the side of someone’s head you’ll notice that the eye curves round the front of the head. Without actually turning the head at all you can exceed what might be assumed to be the outer limits of peripheral vision. There is a visible ground between 90° (approximately the mid-line of either shoulder) and 110° (beyond your shoulder), where straight ahead fixity is 0°. The far peripheral. Out of the corner of your eye.

They told us at school that the far peripheral enabled creatures to move around without turning their heads unduly, to avoid bumping into things and to become aware of threats before they get too close. It is inevitable that things seen out of the corner of one’s eye will often carry a certain weight of menace, usually mild to the point of becoming barely perceptible.

On the other hand, our tendency to misread peripheral information can be regarded as having a survival value comparable to the indisputable advantages of a built-in optical early warning system. It could almost be argued that if peripheral vision generally delivers insufficient detail this actually enhances the survival project insofar as one is compelled to double check just in case one has overlooked a ravening nearby bear, dog or highwayman.

We’re not talking ayahuasca here. This is the straight street, not even the high street. But if the structure of the eye is such that it facilitates both detection and misinterpretation then it is tempting to imagine the capacities of the corner of the eye being extended right across the visual field so that the peripheral eclipses the fixated.

But I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking ‘That’s all very well but how are you going to get to the shops/the cinema/the other side of the room?’ To which I would riposte ‘Yes but is it not conceivable in this case that what would then be seen would be not the consensual external but a marvellous mélange not dissimilar to the dogbear (or beardog)?’

It might be that you would then feel obliged to observe that ‘I am an airline pilot/driving instructor/ person. The only way that would work would be sitting down. And not in an aeroplane. Kindly remove your sewing-machine from the dissecting table.’

The information delivered by peripheral vision is, of course, invaluable but it is also imprecise. If it seems ominous, however, it is not always the case that one need be dogged or cowed by it. You have the option of immediately turning your head and instantly resolving the matter. If you choose not to turn your head then the misinterpretation may linger, which introduces the possibility of savouring the distorted elements connoisseurially: where you do not discard but retain, perhaps in the belief that while it might be distorted it can also be regarded as a free offer.

Saccades: A saccade (from Fr: jerk) is a quick, simultaneous movement of both eyes between two or more phases of fixation in the same direction. Humans and many animals do not look at a scene in fixed steadiness; instead, the eyes move around, locating interesting parts of the scene and building up a mental, three-dimensional ‘map’ corresponding to the scene. (Saccades: Wikipedia) In this example the viewer’s eyes will saccade as they track the movements of the saccading eye.

It’s misleading to conclude that visual distortions of this kind are damaged goods. Along with misheard speech and misread texts they constitute a constant but elusive source of inspiration for artists who are keen to examine the sources of inspiration. All that glimmers is not gold, needless to say. A lot of this stuff is off-cuts. But they who denied it supplied it and should not disdain authorship.

Authors are free to develop their material. Many of them would see such development as a seamless extension of techniques or anti-techniques that they employ as a matter of routine. When paying attention to the suburbs of attention is successful, the event may be called ‘a good idea’ or ‘a brainwave’, something that ‘popped up’ etc.

In the well-known but only moderately amusing joke about drunks: Is this Wembley? No, it’s Thursday. So am I. Let’s have a drink. the rewards of mishearing are made clear. The peripheral becomes the contaminant that enters the mainstream and determines its course.

The dominant contaminant is probably not misperceived so much as overlooked. Everyday thought teems with mental events and is accordingly filtered in order to maintain fixation. The thoughts that don’t fit fall away into the wings. We learned how to ignore them years ago. If we were to unlearn those lessons then the beardogbears could lollop out of the woods and display themselves and if we didn’t like them we could send them packing. It’s like going to the gym (I imagine) – the more you do an exercise the easier it gets.

On the foreshore of the Oxfam Book Shop a mint copy of ‘London in Fragments – a Mudlark’s Treasures’ by Ted Sandling. It’s about the people who dig antique fragments out of the mud when the Thames is at low tide. On Sandling’s first ever visit to the shore he spots a fragment of an old clay pipe and initially dismisses it as being simply too ordinary, as mudfinds go. On closer inspection he is excited to find that the bowl of the pipe is moulded to resemble ‘a perfect horse’s hoof, complete with a fetlock and a fine coat of hair.’ The muddy old pipe stem had been misperceived, its distortion overlooked. A thing of the interior was rejected in favour of the mundane. An inverted surrealisation has taken place: the hunter has construed something as unworthy of remark but upon taking it in hand he sees the commonplace morph into a dream object before his eyes. pipehorsepipe.