First published in GQ 1993

“From now on do exactly as I say,” says PsychoSpy. “And act like you know what you’re doing.” We walk quickly along the carpeted terrace and duck through a service door. “Security doesn’t cover these,” he mutters. Suddenly we’ve left the hubbub behind and our footsteps are echoing as we climb a bright aluminium stairway through a confusion of fat ventilation pipes and wiring ducts. Surfaces are scuffed and dusty, and clumps of congealed brown insulating foam protrude from the walls. “It’s tempting to throw a coin down, isn’t it?” PsychoSpy says, squinting at the sloping inner skin of the building as it falls away from us into the darkness many levels below.

Five floors up we come to another service door. It opens onto a walkway leading directly to the lip of the high terrace. “It’s at this point,” remarks PsychoSpy, “that I start to feel just a tad afraid.” The walkway ends in a sheet of waist-high plate glass. Beyond this is a sheer drop of a couple of hundred feet. Far away on all sides are stacked terraces, their back walls lined with doors, beside each of which are columns of painted hieroglyphics. It’s down on the floor, though, that the most arresting sight is to be found.

Apparently growing towards us like a vast living crystal, is a glistening monolithic structure in black glass. On its near side is a curious jutting prow that partly obscures the tiny figures milling beneath it. Since the huge space we’re surveying is pyramidal, in order to see what else is beneath one’s feet it is necessary to lean out and peer in a dangerous downward diagonal, at which point another incongruity is revealed. Running around the base of the pyramid is a ribbon of dark water, a canal in fact, and on it floats a gondola-like craft. Even from this height it is possible to make out the boatman standing in the bows. He is wearing a tunic and a short skirt. “Aah! That’s the Nile, right?” I exclaim. “Nice, isn’t it?” retorts PsychoSpy, “Shall we lunch?”

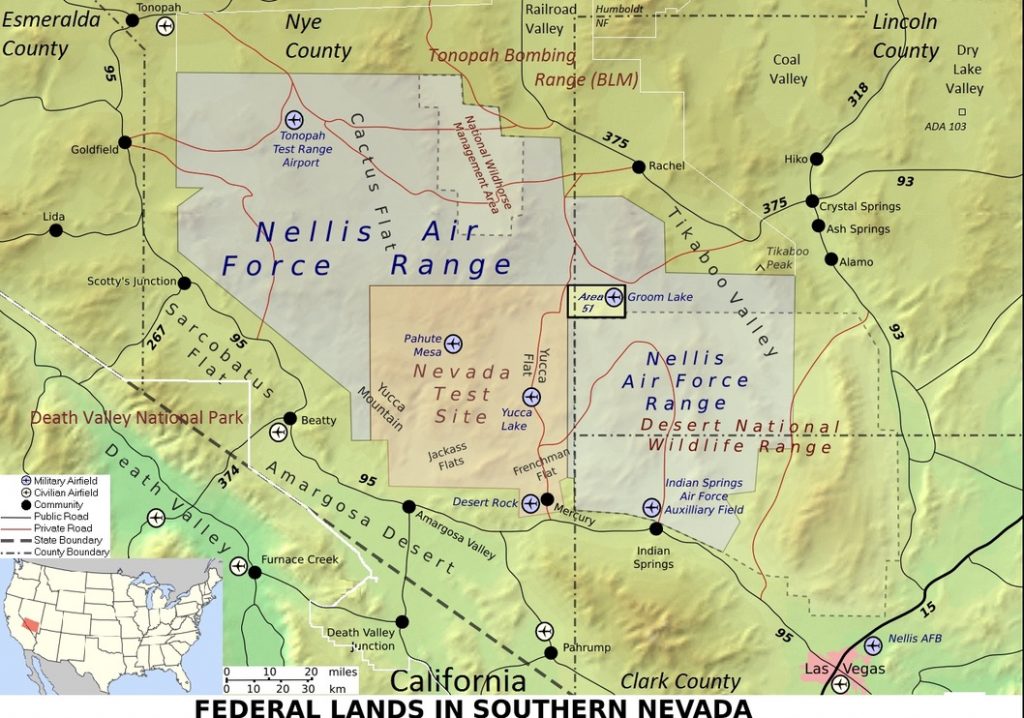

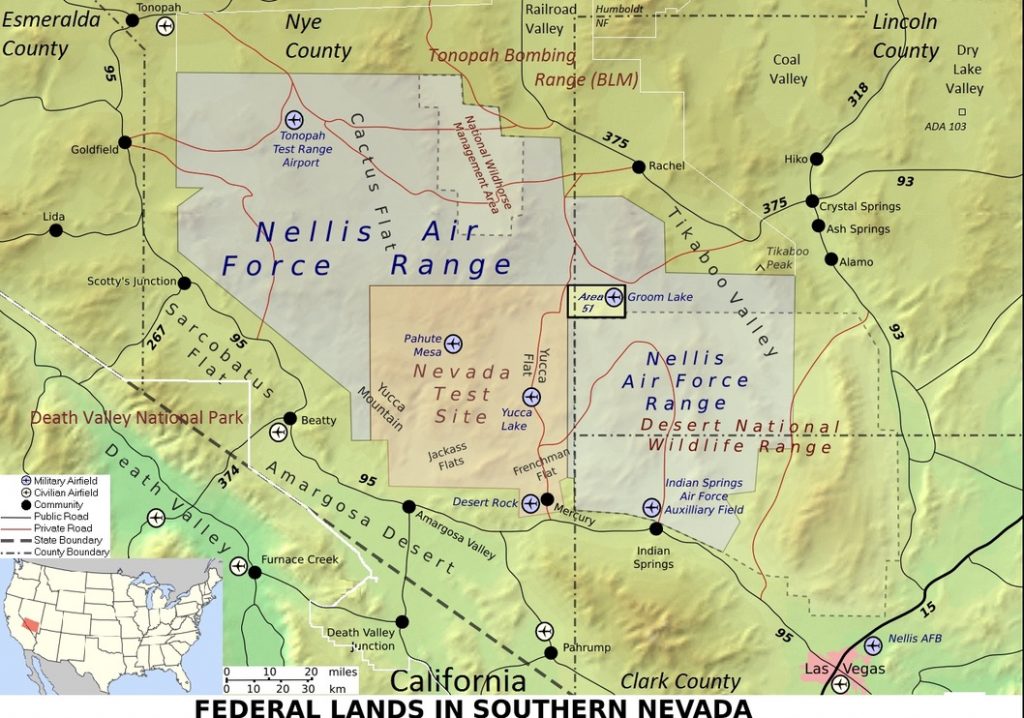

The Luxor Hotel, Las Vegas, has a number of dining spaces, but we choose the buffet lounge, a straightforward eatery in the shadow of the Virtual Reality cinema whose glass exterior we had recently examined from above. The hotel itself is a gigantic scale model of the Great Pyramid, clad in a dark golden glass that’s very difficult to keep clean, so PsychoSpy tells me, with a hint of satisfaction. My companion’s real name is Glenn Campbell and he is Nevada’s foremost expert on Area 51, the legendary ‘Dreamland’ zone deep in the desert wastes north of Vegas. Area 51, which officially does not exist, is the site of the top secret U.S. Air Force base at Groom Dry Lake, itself a small part of the 8 million acre Nellis Air Force Base. It is here that the government is said to be holding the remains of the flying saucer that crashed in Roswell, New Mexico on July 8th, 1947. Some researchers assert that not only alien craft are held in Dreamland – their pilots are there too, engaged in mysterious transactions with the American government. The business at Roswell is the single most perplexing episode in the history of UFOlogy.

After two cans of Diet Coke and a mound of buffet – “Five and a half dollars and it lasts me all day!” – Campbell leads me out into the stupefying afternoon heat, past the silly Sphinx and the unlikely Obelisk, across Las Vegas Boulevard and down to The Oasis, a group of apartment buildings one hundred feet from the northwest corner of McCarran Airport. Kind of noisy, one would think. PsychoSpy has his reasons, however. Standing in the porch outside his front door he points to a building half a mile away across the simmering tarmac. “That’s a secret government terminal,” he declares. “I can watch the JANET flights go out to Groom Lake every morning.” JANET, followed by a flight number, is the radio call-sign used to designate the unmarked Boeing 737s that carry civilian workers on a short hop to and from the non-base.

An ex-computer programmer from the East Coast, Glenn Campbell edits an Internet newsletter (enquiries to PsychoSpy@aol.com) called ‘The Groom Lake Desert Rat’ and its consistently wry, sceptical and inflammatory stories have, in the view of certain government security agencies, put him near the top end of the Most Irritating Man list. Normally a resident of the tiny town of Rachel, Nevada, the closest civilian cluster to the base, Campbell has recently taken an apartment in the ‘centre of the known Universe’, as he unironically describes Las Vegas.

Seated in his apartment beneath a detailed wall map of the Nellis Air Force Base Bombing and Gunnery Range, Campbell insists that his obsession is fuelled partly by a political concern with government accountability and partly by a fascination with the ways in which contemporary folklore is generated. “What the aliens intend, who they are, how many races of aliens there are – that’s quite beyond what I’m prepared to tackle. I’m concerned with only a very simple thing: what is this government program, how is it structured, how does it work and what are the ˜humansˇ doing? I’m only interested in the human story – I have no means of approaching the alien thing itself.” Compared to many of those in thrall to the emanations from Groom Lake, Campbell’s style of surveillance is cool and his conclusions are inconclusive. This is, as we shall learn, a rare condition. There are people out there claiming to have seen things so extraordinary that if they’re true we’ll all have to rewrite our lives from the bottom up.

I was getting a bit pissed off with Vegas. So hot, so crowded. I wasn’t learning from it. Sliding into my Geo Prizm, which is a form of car, I took off for Lake Mead Marina, to get a beer and think about porosity. There is a personality type, I was beginning to feel, that leaks. The membrane between the inner and outer worlds is more than usually permeable, resulting in confusions of perception. Dreams and ideas may seem to originate in the real world rather than the mind. If this never happened, of course, then we would all be restricted to a form of consciousness more animal than human – we’re talking about a matter of degree here. Leakage can be regularly experienced in the most ordinary situations – whenever we feel that someone is shadowing us in the street or lurking in a darkened room we are momentarily giving reality to ideas that may have their origin solely in memory.

Once you buy into the leakage thing, however, it seems you’re fair game for absolutely anything that resides in the inner. Studies of ‘fantasy prone personalities’ – those whose inner lives were highly active and imaginative and sometimes became inseparable from reality – have shown that often a condition called dissociation can develop, in which mental processes may co-exist without becoming connected or integrated. This splitting of the mind can lead, in extreme cases, to multiple personality disorder and at a lesser intensity will generate exotic, detailed and often persecutory visions.

In an extreme version of the porous condition the most fantastical inner events may be projected onto the outer world. The only limits to this process would be cultural: the things ‘seen’ in the world would reflect anxieties about that world and the appearance of the things seen would broadly correspond to contemporary visual realities. Throughout most of the 20th century it has been inappropriate to see fairies, for example. Seen creatures still tend to be small, however, and they still have big eyes. There must be reasons for this.

As you leave the Marina, softened by an hour’s release from the stridently porous architecture of the Strip, you must walk from the bar across a chain of linked pontoons that float in the shallows of the lake. Dusk was falling and the heat had settled to a comfortable 98 degrees. As notions of the phantasmal still circulated in my mind, I became aware of a most peculiar sound. Somewhere, very close at hand, something was sucking. I walked across the intersection of two sets of pontoons and stopped to look around. Yachts bobbing gently, not a creature in sight. The sound was now much louder and it was at my feet. I looked down. Gazing up at me were a hundred pairs of round, unblinking eyes and a hundred gaping, gasping mouths. The mouths were big enough to take a baby’s fist and they were fringed with black whiskers.

Catfish.

Thick velvety bodies squirmed and writhed in the water as the fish strove to elicit the breadcrumbs that passing humans throw them. As I stared down in fascinated horror the picture swung round and I found myself wondering what they saw, what kind of figure it was that loomed in those pale, supplicating eyes.

But where’s the Prizm? Back on dry land I can’t see my car anywhere. Scanning the rows of parked vehicles I double take and realise that I’m looking straight at the car, but something isn’t quite right. It takes a couple of seconds to register: the licence plates have gone! Suddenly the world turns over and I’m seized with a panicking dread. It’s all perfectly clear: Government agents, who routinely tap Glenn Campbell’s phone, have discovered that tomorrow I shall be travelling to Rachel in order to get near Area 51. This is their message, just like the one they left in the car belonging to Bob Lazar. Without licence plates I’m a sitting duck, a plaything for the Highway Patrol who can bust me whenever they feel like it.

George Knapp is a reporter and newscaster with KLAS-TV in Las Vegas. In 1989 he was approached by John Lear, a colourful UFO researcher who had claimed, among other things, that praying mantis-like aliens, more advanced than us by a billion years, were providing the Government with their technology in exchange for the right to conduct genetic engineering experiments with our womenfolk. Lear told Knapp of a man called Bob Lazar who had worked in Area 51 and had something of a tale to tell. Knapp tracked down Lazar and set up a TV interview that had sceptics catching their breath and the credulous on their knees weeping with relief.

So I’m sitting there with George and he seems a perfectly rational, collected guy – a no-bullshit professional investigative reporter who has spent years dealing with conmen, fraudsters and your bottom line delusionals. And George buys it. He believes it when Bob says we are not alone. Something starts to shift inside me. What if…? Oh, but surely not! You’ll be an abductee next! It must be the heat.

As we stroll out to the studio foyer George tells me that Bob Lazar was a scared and reluctant interviewee who had intimated more than once that people were out to silence him. On one occasion, Bob, who carried a hand-gun in the glove compartment of his car, left the vehicle in a parking lot for the day. When he returned the trunk, the hood and all four doors were wide open. The glove compartment was open too, and the hand-gun was just sitting there, for all to see. George went over to Bob’s place a while after that and Bob wouldn’t open the door. George convinced him it was alright so Bob started sliding back the bolts. The door opened and Bob stood there sweating with fear and clutching a Uzi submachine-gun.

“We put Bob on the air, blacked out his face and asked him who he’d worked for and what he’d seen. And he told us. He’d been out at the location called S-4, south of Groom Lake, at Papoose Dry Lake bed, and it has this series of interconnected hangars and inside were the nine flying disks, what he called ‘The Variety Pack’. I thought ‘If this were true it could be the story of the century.’” Yes, but what about corroboration? “I’ve found a lot of it. In the six years since the story broke I’ve had more than two dozen people who’ve had bits and pieces of the same story – people who worked there through the fifties, sixties, seventies and eighties, people who didn’t know each other or that each was talking to me.”

Back at the hotel in Vegas I can’t get to sleep. The air-conditioning is shot and my personal porosity reading is at colander level. I open my eyes and instantly go rigid with terror. Floating across the room towards me is a six foot high, multi-faceted red diamond. It stops at the foot of my bed and hovers. It’s the Whitley Strieber author of “Communion” (1986) thing! Little grey guys with big eyes are about to do sex operations on my mind! The government is in league with creatures from the Pleiades! I sit bolt upright and blink insistently. The diamond disappears. I leap out of bed, put the light on and gaze at the ceiling. The tiny red light on the smoke detector is designed to blink on and off at regular intervals to signal its readiness. The insomniac eye distorts small points of light.

8 a.m. at Alamo car hire. “Yeah, they steal the plates all the time. Put them on their own vehicles so’s they don’t have to pay.” He gives me a very big Buick to make up for my disappointment. I love him and want him to come on holiday with me. Ten miles up Route 93 en route to Rachel, the speedometer cuts out. I’m driving alongside Nellis Air Base. Scrub, sagebrush and Joshua trees stretch to the horizon in all directions. Not a car to be seen. Off to my right is a range of parched grey hills. Three helicopters flying in echelon hurtle out of a ravine and take up a position four hundred yards away and about a hundred feet up, just over my shoulder in the blind spot. Without a doubt it’s the Jim Keith ˜Black Helicopters Over America˜(1995) thing, where the notorious conspiracy researcher and Patriot Movement sympathiser documents ‘the mysterious phenomena of black helicopters which have been seen all over America and often linked with mysterious troop movements and shipments of war material and strange things which are taking place in terms of a consolidation of the new world order’!

I peer casually over my shoulder. Okay, so they’re not black, they’re dark green. But they’re definitely trailing me. After about ten minutes during which I adhere faultlessly to the speed limit, the ominous escort moves ahead, flies a mile down the highway, crosses in front of me and hovers eight feet off the ground about a hundred yards from the road. I drive through the dust cloud affecting nonchalance. The choppers let me pass then vanish into the hills.

Hours of scrub later I come across a settlement of about fifty mobile homes, one gas station, a general store and a bar. This is Rachel, pop. 100, elev. 4970, gateway to Dreamland. Glenn Campbell’s Area 51 Research Center is a battered brown trailer set beside a small lawn on which are playing three blond children and two dogs. Running the office in PsychoSpy’s absence is the mother of the kids, a waif-like young woman called Sharon Singer. I ask her what she makes of this UFO business. “You sure you wanna know?” Definitely. “Okay. I’m a Christian and I believe that the aliens are part of the fallen troops of Satan. They are demons sent here for the final deception of the world. The New Age movement is telling people that there’s gonna be a planetary cleansing and that they’re gonna remove the menaces to society and I believe they’re gonna to tell their people this after Jesus Christ returns and takes His body home – takes the Christians up to Heaven – and that’s how they’re gonna explain this away, they’ll say ‘Oh, the UFOs took’em, they were a menace to society, now we can go on with human evolution, now we’re Gods.’”

Sharon, I wonder if you could just run that last bit past me one more time? “Yeah. This UFO thing, it’s the biggest lie that’s ever been. They come from the Second Heavens, that’s where Satan and his troops abide, that’s their domain, and I do believe that they’re actually there.” Where is Second Heaven? “That’s from where the ozone layer stops. It’s outer space.” So what happens to the non-Christians who don’t get to go to First Heaven? “Okay, the Christians will go for a seven year party, in Heaven – the Wedding Feast – and the people here are gonna be left for the seven year Tribulation, where the AntiChrist will reign. It’s gonna get hard here on Earth, you’re gonna have to have the Mark of the Beast in order to buy, sell or trade. Then after seven years Satan will be locked up and Jesus will hold the key.”

Over at the Little Ale’Inn – Earthlings Always Welcome – proprietress Pat Travis deepens the theme. First of all, though, she indulges the ritual that must preface all conversations about flying objects: the citing of the sighting. “A beam of light came through the centre of our back door, that’s a steel-clad door. It was not an open door, it came through the metal itself as if someone had walked through with a flash-light, but a big one. It illuminated the whole door-jamb. I knew that there were beings in our room. Prior to this we had talked about selling our business and the next day I mentioned it again and my husband said ‘But we’re not selling this – last night you told me that the beings do not want us to leave yet.’ To this day I have no recollection of this at all – he said it was me talking to him but I feel it was them talking to him through me.”

Pat believes there are definitely live aliens on the Groom Lake base, a belief which is, if you like, Level Three on the Dreamland scale. At the first level you believe that the base is simply a testing ground for highly advanced military aircraft. Subscribers to Level Two know that the flying disk that crashed in Roswell was an alien craft ultimately transported to Area 51 for reverse engineering trials with the likes of Bob Lazar. At Level Three, however, not only did the disk crash on the debris field at Foster ranch near Corona, New Mexico (actually a ninety mile drive from Roswell itself), but it then limped on to the impact site on the San Agustin plains west of Socorro, crashed again and disgorged five alien passengers. An addendum to this narrative has escape capsules from the damaged craft being found at a third site just north of Roswell, also with aliens on board. The only alien to survive the journey went on to work with the US Government.

Extensions to the Level Three belief shade across into a very dreamy land indeed, where porosity meets paranoia and generates theories of conspiracy so intricate and comprehensive that it seems as if all that is unknown is uncannily linked in a devilish lattice comprising a hidden underworld of deception. This is an ethereal place where haunting landscapes, vast empty spaces and heavy handed government secrecy constitute a psychoactive force that dissolves the membranes of the mind so thoroughly that the inner becomes hopelessly lost in the labyrinths of the outer.

While Glenn Campbell, for example, moves gingerly through this mythic territory, protecting himself with invocations of his academic and folkloric concerns, there are increasing numbers of Americans who have been swept away from the shoreline and are not waving but firing. Pat Travis, clearly not a militant herself, does nevertheless articulate the vector that runs from UFOlogy to an extreme libertarian view of government. It will, she feels, not be long now before the truth about aliens is publicly admitted at the highest level. “But what they’re gonna try and do is say that they’re invading us. And they’re not invading us. The idea is to bring everybody into the circle of the One World Government that they’re trying to pull off on us now. The United Nations are trying to do this and the banks are involved. I don’t believe it’s the US Government per se, I believe it’s…they.”

UFOs as State Theatre. It’s a plaint I’ll hear right across the West. Many people believe it and a handful are acting on it. That’s Level Four and ultimately it leads to Oklahoma. Before I leave Rachel, though, there’s one more thing I have to do.

With Glenn Campbell’s ‘Area 51 Viewer’s Guide’ (a snip at fifteen bucks) beside me in the car, I head south out of town on Highway 375 until I reach the Black Mailbox. The latter, a meeting place for the steady stream of UFO nuts who pass through the area, is described by Campbell as ‘a religious site for True Believers’ and many sightings have been notched up in its vicinity. Most of these are flares dropped during war games exercises, asserts the author, and the mailbox itself is more useful ‘for the busloads of Japanese tourists or anthropologists who want to observe the True Believers.’

A dirt road runs into the desert from the mailbox and after about four miles meets up with Groom Lake Road, which leads directly to the non-existent base. The Buick does pretty well on the bumps, any of which may occasion a jolt to be picked up on the illegal sensors buried by the military in the roadside dirt. If detected, the visitor can look forward to the sight of the ‘Camo Dudes’, security patrols in white Jeep Cherokees who will peer at him through high power binoculars from a ridge within the bounds of the base.

Eight miles later, having paid adhesively close attention to the list of landmarks in the Guide, I slow the car to a crawl. The Guide is explicit: ‘The Border – Restricted Area begins in a blind ravine, just before the road turns a corner. There is no fence or gate, just a half dozen warning signs on either side of the road.’

Eight miles later, having paid adhesively close attention to the list of landmarks in the Guide, I slow the car to a crawl. The Guide is explicit: ‘The Border – Restricted Area begins in a blind ravine, just before the road turns a corner. There is no fence or gate, just a half dozen warning signs on either side of the road.’

Right foot hovering above the brake pedal I roll into the ravine. On either side of the road is a large white sign. In recovery from a recent bout of porosity fever I cautiously approach the signs by foot and take advantage of my extreme long sight to read their legend. ‘It is unlawful’, I gather, ‘to enter this area without permission of the Installation Commander.’ At the bottom of the sign, in red, is a disincentive for the cheeky chappie: ‘Use of deadly force is authorized.’

That’s it then. Off to Roswell now, a thousand miles to the east. As I’m bypassing Vegas, the speedo comes on again. Get thee behind me, transmembranous leakage, we’re going back to the 40s where it’s perfectly safe!

Later that night I check into the Hill Top Motel in Kingman, Arizona, an old Route 66 town. The proprietor is a fan of ‘Coronation Street’ and has a signed photograph of Molly Sugden. “Maybe you’d like Room 119,” he says. Why’s that? “Oh, Timothy McVeigh stayed there for five days while he was planning Oklahoma.” Wow. “Yes, a very nice young man, very, very nice. Very polite. And so tidy, he even made the bed in his own room. My maid said the sheets were so tight she could barely move them. Just like he learned in the army.” Perhaps I’ll have 118. “You sure? We had the FBI crawling over that room.”

The mournful whistle of a Santa Fe freight train rolls through the warm night as I float in the motel pool. Why didn’t I take 119, for Heaven’s sake? I could have dined off it, I could have written about it for GQ! It’s porosity again – McVeigh has left a taint of derangement in the room and I don’t want it to infect me. My conversations in Rachel had been so dreamy that my own osmotic shortcomings had, up till this moment, seemed quite manageable. Just who are the fallen troops now?

Leaving Highway 40 at last and heading south down what must be the longest, straightest road in New Mexico, I find myself, every couple of hours or so, overtaking camouflaged camper vans. The drivers invariably wear camo peaked caps and full fatigues, as do their passengers in the back. The ponytails and straggly beards indicate that we’re not talking US army here. Maybe they just have a rugged love of the outdoor life.

South of the windswept hamlets of Encino and Vaughn with their crumbling clapboard store fronts, smashed gas pumps and deserted, peeling motels, the landscape becomes wholly featureless, unless sagebrush and the odd wandering steer still count as a visual occasion. When least expecting it I catch sight of a sign pointing into the desert. Slamming on the brakes I’m gratified to find that this is the road to the ‘UFO Crash Site 1947’. Parked just off the road is a battered four wheel drive. Seated inside is Hub Corn. For fifteen dollars, Hub tells me, I can get a guided tour of the Impact Site. As it happens, he is waiting even now for a party of tourists to arrive, so why don’t I join them?

The release form enjoins me to ‘realize that being on a ranch in the desert may be a hazardous activity including, but not limited to, snakes, scorpions, cactus, lizards and other wild animals, and I hereby accept any and all risks associated with that activity.’ Having released my host, a genial rancher in his early thirties, I follow the 4WD as far as a flooded creek where we find that Hub’s wife Sheila has already assembled the day’s tourists. Two schoolteachers from Amarillo, Texas have brought four silent, sunburned children out to see one of the two, or maybe three, most important places in the world. Also bunched by Sheila’s 4WD is Ron, an amateur UFO researcher from California, accompanied by his son.

We pile in the pickups, squelch through the creek and follow a track over low scrubby hills studded with shattered boulders. Hub explains that he’d gotten so irritated at chasing trespassing UFO nuts off his ranch that he’d decided to give in and make a buck instead. There’s been a big conference in Roswell earlier in the year so Hub had got the bulldozer out, dug a road and levelled out a car park. Business had been brisk.

A corridor of rope hung with blue and white pennants leads from the park to the site. We trudge through the heat and fetch up at a wooden railing. And there, a dozen feet away, halfway down the face of a low ridge is…a bunch of rock. Just like the rock next to it. What you have is some rock, right, and halfway down it some orange and blue paint marks, put there by Hub. They show where the UFO hit.

We stare silently at the rock. I steal a glance at the schoolchildren. A couple of them are looking at their shoes and the smallest one is gazing distractedly at the sky, showing early signs of heat stroke. Ron asks a number of perfectly reasonable questions about angles and so forth. Hub delivers answers in a slow drawl. Sheila holds up a parasol but no one will step into its shade. Minutes pass. The schoolteachers’ eyes wander increasingly off target. A gangly teenage boy with a camcorder covers every exchange, panning abruptly into the crowd whenever someone thinks of a new question. After what feels like many hours but is probably fortyfive minutes, Hub says “Well, if there are no more enquiries.”

Back at the creek, two miracles have taken place. The schoolteachers’ car has developed a flat tyre and Hub and Sheila’s dog has had two puppies. The children, looking uncomfortably baked by now, suddenly become very animated and poke at the puppies with delight. Hub gets under the schoolteachers’ car with a big jack.

Roswell, far from being the grey and dusty stage set of my daydreams, is a bright and bustling town at odds with its location in the middle of nowhere. It has two UFO museums, both packed with maps, photos and texts about The Incident. At the International UFO Museum eager patrons squeeze past each other bearing notebooks, cameras and dictaphones, while the Visitors’ Book attests to the global allure of flying disks. When I boast to the receptionist of my trip to Area 51, several pairs of eyes glance enviously in my direction and a longhaired man in denim overalls approaches with a solemn warning. “You know, they take these energy signatures now. If you get out of the car they have this device that can record a man’s energy, it takes about seventeen seconds. If you ever go back there they’ll compare your signature to the one they have on computer, to see if you’ve been there before.” Fine with me, friend, I’m not exactly figuring to go back.

Robert Shirkey was a First Lieutenant and Assistant Operations Officer in the USAAF in 1947, stationed in Roswell with the 509th Bomb Group, then the only outfit in the country licensed to carry atomic bombs. Today he is invigilating at the Museum and consents to what he jocularly claims is the day’s 43rd interview. Like many of the accounts available from Incident veterans still resident in the town, Shirkey’s testimony is teasingly slight, a mere fragment of the picture that dedicated researchers claim to have put together from dozens of overlapping stories.

“Colonel Blanchard came in after lunch and asked ‘Where’s the B-29, is it ready to go?’ We said yes so he stepped into the hallway and waved to some people and they came walking through. I asked Colonel Blanchard to turn sideways in the door so I could see too. Perhaps I shouldn’t have done that. We watched these people walk through the hall onto the aircraft and several of them were carrying open boxes of material. I saw a cardboard box with pieces of what looked like aluminum foil and I saw the I-beam sticking up in the box that Major Marcel was carrying and I could see that it had some sort of hieroglyphic writing on it. Today I cannot tell you what they were.”

Weather balloon or UFO? Maybe the papery metallic fragments were scraps of then unfamiliar neoprene plastic developed for top secret Project Mogul balloons, destined for high altitude spy flights over Russia to detect nuclear tests but launched experimentally from nearby Alamogordo Air Field throughout June and July of 1947. Maybe the hieroglyphics were simply the flowerlike designs on the reinforcing tape used on the Mogul radar reflectors, designs printed on the tape in the New York City toy factory from which it was obtained. This is the view of the American skeptical movement and sounds rather mundane, undreamy and conclusive.

Weather balloon or UFO? Maybe the papery metallic fragments were scraps of then unfamiliar neoprene plastic developed for top secret Project Mogul balloons, destined for high altitude spy flights over Russia to detect nuclear tests but launched experimentally from nearby Alamogordo Air Field throughout June and July of 1947. Maybe the hieroglyphics were simply the flowerlike designs on the reinforcing tape used on the Mogul radar reflectors, designs printed on the tape in the New York City toy factory from which it was obtained. This is the view of the American skeptical movement and sounds rather mundane, undreamy and conclusive.

Heading back to Las Vegas to catch my plane, I travel north of Alamogordo, past White Sands Missile Range and over onto the Plains of San Agustin, where some respected researchers claim that, back in 1947, a number of people watched as a wounded and terrified alien crawled from a second crashed craft. At the western edge of the Plains the bare landscape is broken by long lines of towering white radar reflectors arranged in a Y shape. Known as the Very Large Array, the installation consists of twenty-seven eighty foot steerable dishes set in thirteen mile lines. The radiotelescope is listening to the stars, picking up signals from deepest space. Climbing over the wire fence between the VLA and the highway is a man in combat fatigues, carrying what looks like a powerful crossbow. Parked at the roadside is a camo van. The rear doors are open and two bearded men in fatigues are standing beside them.

Bill Cooper, Managing Director of the militia newspaper ‘Veritas’, a copy of which I purchased from the Little Ale’Inn in Roswell, is also a prominent UFOlogist of the high conspiracy persuasion. Earlier this year in an article for his paper called ‘The Truth About Militias’, he wrote “A nation or world of people who will not use their intelligence are no better than animals who have no intelligence. Such people are beasts of burden and steaks on the table by choice or consent. Find and join a militia or form one of your own.” Not wishing to become a steak on a roadside table, I use my intelligence to drive right on past the camo van and its troops without, I trust, more than an imperceptible sideways glance. What didn’t go away, though, is the question of just what the patriots were up to. If they suspect that the Government is about to orchestrate an alien invasion in order to enforce the New World Order – a nightmare of national and racial porosity – then maybe I had witnessed a crack redneck cadre casing the VLA in a bid to cut the lines of communication between Earth and the Pleiades. Or maybe they were after jackrabbit.

The prospect of contact with extraterrestrial life is, quite simply, enchanting. For most of the UFO community the enchantment is benign and, if one subscribes to a psychological view of folklore, the leakage from the inner onto the outer is directly comparable to those medieval processes that led to the evolution of stories of faerie in which wise, generous and magically assisted beings helped us to manage our lives with greater insight. Just as many stories, however, refer to malevolent, bewitching entities who would enjoy casting us into pain and confusion for eternity.

So is this a way of saying that there is a new medievalism abroad? Of course not – it never went away and has ever been thus. When the aliens do arrive, as they surely will, one of their first tasks will be to wake everybody up to the 21st century.

Eight miles later, having paid adhesively close attention to the list of landmarks in the Guide, I slow the car to a crawl. The Guide is explicit: ‘The Border – Restricted Area begins in a blind ravine, just before the road turns a corner. There is no fence or gate, just a half dozen warning signs on either side of the road.’

Eight miles later, having paid adhesively close attention to the list of landmarks in the Guide, I slow the car to a crawl. The Guide is explicit: ‘The Border – Restricted Area begins in a blind ravine, just before the road turns a corner. There is no fence or gate, just a half dozen warning signs on either side of the road.’