First published in The Observer 2006

July. The wires are humming. Early signs of impending confabulation are starting to trickle through the aether. Browsing Pynchonomanes, or those of an excitability approaching that condition, are alerted to a listing on Amazon.com. There, running above the usual details for Thomas Pynchon’s classic novels is a 270 word blurb for a brand new book by the cult writer who is so determinedly elusive that he makes J.D. Salinger look vulgarly available. Not only does the blurb disclose themes and events in ‘Against the Day’ but it appears actually to have been written by Pynchon himself.

A day later Amazon had pulled the text, probably at the behest of Penguin Press U.S.A. The move came too late – a Pynchonist had saved the text and reposted it – onto Amazon’s own Customer Discussion Board. It is there today. Here is the first paragraph:

‘Spanning the period between the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 and the years just after World War I, this novel moves from the labour troubles in Colorado to turn-of-the-century New York, to London and Gottingen, Venice and Vienna, the Balkans, Central Asia, Siberia at the time of the mysterious Tunguska Event, Mexico during the Revolution, postwar Paris, silent-era Hollywood, and one or two places not strictly speaking on the map at all.’

Over at the Pynchon-L internet mailing list the lid comes off. The subscribers, hardcore textual stalkers to a man (there seems to be only one female subscriber), some of whom have been discussing the finer, often vanishingly finer, points of the oeuvre for years, go into overdrive. One of the topics discussed was the significance of the cover design, visible on the Amazon page. On the bottom left hand corner of an otherwise rather plain dustjacket is the image of what appears to be a seal or official stamp, depicting what might be mountains, encircled at the seal’s circumference by lettering in an unfamiliar script. The subscribers get to work: there’s a snow lion in front of the mountains; the mountains resemble giant adenoids; it’s not a seal, it’s a coin; the coin is a forgery; the script is Tibetan; it’s a Tibetan wireless telegraph stamp; the dustjacket is referencing either reincarnation, time travel or tripolar disorder. Remarkably, a subscriber unearths a photo of a 19th Century Tibetan coin that closely resembles the enigmatic original.

Why doesn’t this sort of thing happen to Ian McEwan? Because he gives interviews and allows photographers to take his picture and does readings and signings and festivals and the rest of it. Pynchon does none of these. He has never been interviewed, there are only three photographs in existence, all dating from his teens and early twenties, the most basic biographical facts are still a matter of dispute and those that pass muster have been excavated with difficulty. In consequence, speculation runs unfettered and, in particular, the desire to See What Pynchon Looks Like is, among Pynchonians, urgent.

There is, of course, rather more to it, otherwise we would have uncovered the simple secret to success: disappear. Pynchon received the National Book Award for ‘Gravity’s Rainbow’ in 1974 and in 1988 collected the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship award, or ‘Genius Grant’, which guaranteed the Fellow $310,000, paid over five years. He is regularly rumoured to be in line for a Nobel literature prize. His first novel ‘V’ (496 pages), published in 1963, displayed an array of stylistic, linguistic and structural idiosyncrasies that set the stage for a long career in which complex, complicated, insistently thematised works were routinely conflated with fantasies about the author who, one supposes, initially absented himself in order to forestall such fantastication.

The book is a quest-driven episodic account of the attempts of Herbert Stencil to locate V, who is probably a woman. The quest criss-crosses with the escapades of discharged sailor Benny Profane and a troupe of amiable, drinking rascals, the Whole Sick Crew. V may or may not be found and the comical character names may suggest that nothing is to be taken too seriously. This, however, is to discount Pynchon’s prime compositional strategy, reflected in his magnum opus ‘Gravity’s Rainbow’ (768 pages), in which allusion and digression proliferate, a Tarot-like section structure is introduced, structure in general complexifies, 400 characters are deployed and the priapic Lt. Tyrone Slothrop reluctantly learns that his sexual dalliances coincide geographic¬ally with the impacts, a few days later, of V-2 rockets on war-time London.

The novels feature light, busy surfaces, characters who are often more personality than person, narratives impelled by event rather than the inner dynamics of principals – characteristics which seem to point away from substance yet invariably encase an elaborate architecture of political, historical and scientific concerns. The politics are warmly supportive of labour, history is a melange of remarkably detailed research and utter fancy informing a science in which trajectory, explosion, wave forms, light, quantum theory and higher mathematical conundra are all found to have their counterpart in human affairs.

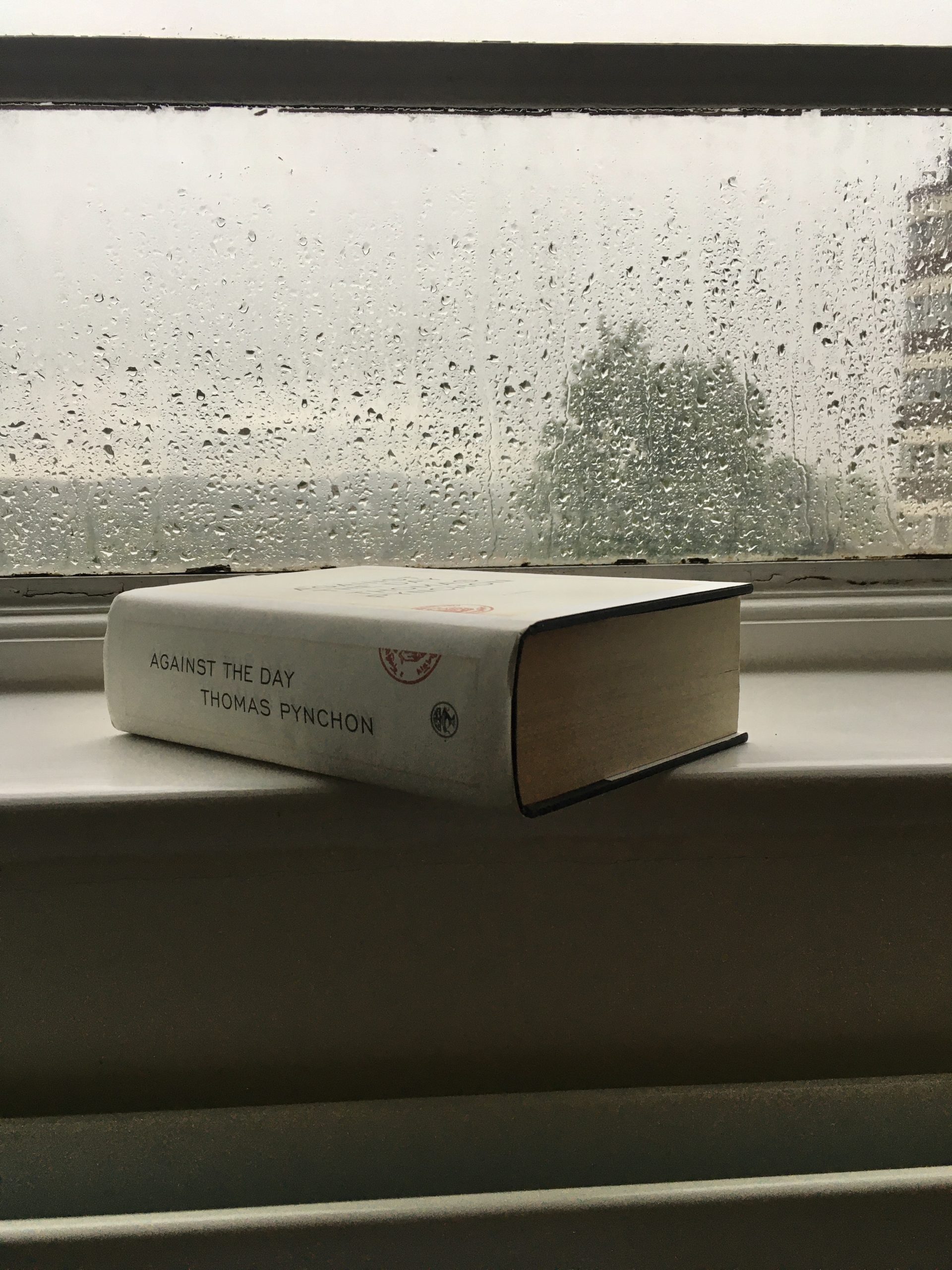

If these sketches suggest elements of Pynchon’s experimental, anti-narrative tendencies then the latest novel, ‘Against the Day’ (1085 pages), sees them in full-blown, runaway metastasis. All that is glorious and exhilarating about Pynchon is found here but the problems of scale are taxing. There is a spinal story of sorts: 1890s cowboy and anarchist bomber Webb Traverse is killed by hired guns in the pay of plutocrat Scarsdale Vibe. His four children – Frank, into revolutionary politics and bombing; Reef, a reckless tunnel blaster wandering the Balkans as Europe shudders into war; Lake, who marries her father’s assassin and Kit, a Yale and Gottingen educated mathematical prodigy preoccupied with arcane and unsolvable formulae – take up the question of vengeance with varying degrees of dedication.

Blessed with droll, laconic cowboy dialogue, the Traverse children and their partners in restless travail are tracked through the thickets of the novel, regularly abandoned then picked up again. Their appearances provide, if not structural succour, then a regular buffer against the seething, overly diverting profusion of other characters and their escapades.

The text is overwhelming, unstable, encyclopaedic and extravagantly allusive. Characters bejewelled with such names as Ruperta Chirpington-Groin, Oomie Vamplet, the Kieselguhr Kid, Darby Suckling, Oleander Prudge and Sloat Fresno are variously implicated in at least a dozen parallel and interweaving accounts that feature such beguilements as a train that travels through sand under the surface of deserts, a dog that reads the work of Henry James, a previously unmapped district of Chicago, a near drowning in a quantity of mayonnaise, the performance of an operetta titled ‘The Burgher King’, a sentient ball of ball lightning called Skip and an air balloon crewed by boyish adventurers known as the Chums of Chance.

The reviewer resorts to lists. In the absence of conventional connecting tissue and the presence of a thousand episodes, impressions are pointillised. At times the author seems burdened with a surfeit of research material and discharges it, at regular intervals, into long scene-setting paragraphs that simply list the contents of rooms or environments. That these contents are generally exotic does not preclude their coming to resemble, after, say, the eighth time, a hardware catalogue or a set dresser’s check list. When objects, gadgets and inventions simply strut across the scene, Pynchon joins company with the neurotic French proto-surrealist and novelist Raymond Roussel, whose highly schematic books feature a dry ingenuity applied to the repetitive description of absurd machines.

None of this detracts from the unique pleasures of a mighty novel that will delight Pynchonians and seduce newcomers. The latter should be prepared to put about a month aside at two hours per day five days a week. The scale of the novel induces memory loss but as with balloon flight, fever or holidays, the return to terra firma is accompanied by feelings of wise, wide contentment. Beneath the disconnected pointillism, skirting the excision of character development, lies an energetic universe through which waves of history, light, time and number flow, at times in concert, at other times colliding. Their collisions coalesce into the interference patterns that are the novel’s episodes and events.

Given that arcane, embedded codes pervade a Pynchon novel at every level, it is instructive to consider the episode in which Reef Traverse is about attempt penetrative sexual intercourse with the lap-dog Mouffette. The episode occurs on page 666, which is the Number of the Beast. Hey.