With Vacant Possession

When I was a kid I would routinely project myself into the places depicted in my illustrated books. Now my kids, in addition to the books that they voraciously consume, have the added option of a trip down the road to a darkened hall in which they can strap on a 3D prosthetic imagination and frolic with lithe alien archery virtuosi whilst bathing in wraparound edenic menageries that abound in gorgeous plants. There are, doubtless, debates to be had about whether such omnivorous entertainments stunt or inspire the fledgling imagination but I can’t be bothered to pursue them.

Other commentators have efficiently disparaged ‘Avatar’s GCSE econarrative leaving the way clear for a consideration of the business of ecstatic technologies and how they interlace in this pioneering product. The movie, obviously, has at its narrative hub a prosthetic virtual sensorium that doesn’t deliver movies or out of the body experiences so much as a totally alien point of view, wherein the ‘alien’ is not on another planet but, more or less exotically, can be located in the person sitting next to you. The trainee transpersonators could just as easily plug into each other’s experience as they could into that of an extraterrestrial. Instead of going to the pub with a friend you could, presumably, go in him or her. The question of who would be the designated driver is interesting: if you’re going for a ride in another person then your host is the driver. If you are able to overrule your ride then you are the driver.

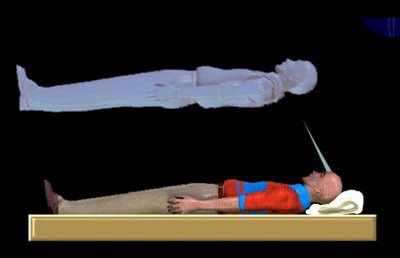

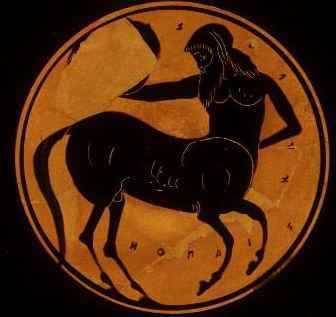

Such a distinction, in ‘Avatar’, is blurred. Our sympathies with the Marine who ‘goes blue’ would be diminished if he seemed to emulate a parasitic brain-worm that munched out his host’s agency. That would be rather suggestive of American imperialism. Instead, paraplegic Jake runs his new alien body but the latter is a genetically engineered copy of a member of the alien race, not an alien who has ever had any experience. The copy is vacant until occupied by the transpersonator, who vitalises the zombie fleshcart. Cameron proposes the jockey mode or, more accurately, the centaur situation, in which the human element is both rider and ridden, driver and passenger. There is no timeshare option whereby two drivers might assume co-pilot status.

Presumably if Hobbits or technopixies had constructed the ecstatic apparatus it would be more readily accepted as empathy facilitation hardware. The software element must be regarded as still in beta, insofar as it can detach then transfer and implant consciousness but not effect the coveted mindmeld that would enable the passenger to sit in the cockpit next to the pilot and be as one with him in a hearts and minds kind of way, as distinct from merely being privileged to see how he does things.

As a cinema of the present offering a 3Dimensionalised window onto the possibilities of ecstatic technology the movie boasts of its own cinematic technofuture, promising a level of immersion that will bundle in the tactile, the olfactory and the gustatory alongside sight and sound. It’s only a matter of time, we are predictably assured. One can sympathise with James Cameron at this point: the cinema screen is such an intractable tissue. It’s actually made of finely punctured, beaded fabric but we cannot travel through the punctures and scamper about. In this respect a prosthetic imagination is a bit of a dumb animal – it can’t make things up. That’s what an artificial intelligence might do. One day (yeah yeah).

When I was a kid I could climb through the frame, turn the corner and make up what I wanted. At the point where the cinema screen empties out – equivalent to Truman (of the eponymous Show) finding that the horizon of his world is a vast cyclorama screen – ‘Avatar’ offers a zipless body transfer when what we really need, especially if we want to migrate to an edenic virtual and never come back, is the reassurance of an authorship that enables us, in our new flesh, to adventure indefinitely.

If the new flesh is merely an armchair with legs then we are at the mercy of book, comic, videogame or feature film parameters. The limitations are considerable: there are moments in ‘Avatar’ when Jake and others are simply unplugged by their human directors, at which point their blue alien giant falls insensibly to the ground. We have reached the limits of cinema. James will probably crack that if he can secure the GDP of a failing state for his next budget.

As a strategy for a life to be conducted within the tyrannical, luxurious embrace of hyperconsumerised capitalism, however, ‘Avatar’s prescription is dandy. Within ten or twenty years the problems of agency will be so pronounced that the objectless, uterine worlds of the gorgeous virtual will be much in demand from those of us seeking a final solution to the onerous business of driving an ever more eviscerated meatbuggy.

03.02.2010