David Gale’s Peachy Coochy Nites #10

20 slides are each projected for 20 seconds and spoken to for the same period, no more, no less. The script for one of these precision-based presentations is found below.

Season 1: PC#10

Previously on Peachy Coochy I had continued in my attempt to dispel any quality of fiction in my presentations, adopting an unadorned style in which the clumsy attempts to obscure the autobiographical would be replaced by a transparent directness. I noticed, for example, the preponderance of images of larvae, grubs, beetles, insect eggs and maggots in my repertoire.

I was aware that, for me at least, they represented abject levels of consciousness: all that was most repellent and shameful in my sense of myself. In Peachy Coochy Number 9, for example, I alluded explictly to my attempts to sever contact with my shame, going as far as leaving it to languish in a house in Hertfordshire.

People say to me “What is it about Hertfordshire, David? You seem to regard it as the arsehole of the south-east. A repository for that which must be relinquished, a terrain of aching boredom, a place where, after mixing Red Bull with Wifebeater, disconsolate late-night youths wrench bus-stops out of the ground and propel them through the window of the doner kebab takeaway.”

“You said it, not me,” I tell them. The desolate eventless core of the county is to be found in Royston, where, for several days, I installed myself in a B&B near the Sports Centre. Lady Roisia founded the town in the 11th century, erecting a cross on a boulder at the junction of two ancient tracks. The Royse Stone, as it was known, is a glacial erratic.

Instantly I realised the significance of my appalling sojourn. A glacial erratic is a stone deposited far from its place of origin by a glacier. There is no question of return. There are no trucks big enough and nobody can be bothered anyway. Why would you tidy up that which nature has in her wisdom wrought? I decided to go to the BackPacker Pub in King’s Cross.

I wanted to squeeze between shouting Australians and hoist foaming tankards in amiable anonymity. The pub had changed hands and was now called the Cross Kings. The cultural historian and mythographer Marina Warner was drinking mineral water by the window. I admired her work greatly and asked her to sign my wrist. She asked about my maggots and suggested that they could be seen as emblems of possibility.

In the back garden of my house I have a sizeable shed where I keep the objects that I photograph for the Peachy Coochy presentations. You can see a wicker chair through the glass door there. When I got back from the pub I went in and instantly reeled back in horror. There on the chair, seething with maggots, was the denuded body of my songbird Celine, named after the singer Celine Dion.

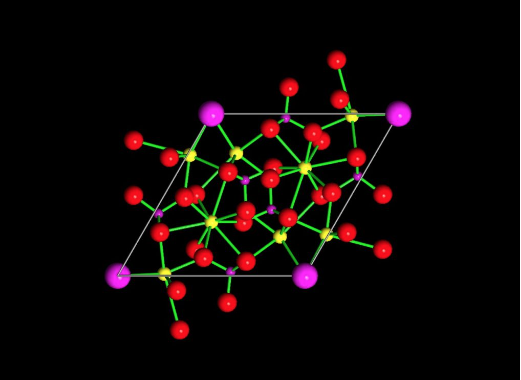

A great rage welled up within me. Even in that moment, however, I was able to remind myself of what Marina had told me. I crushed Celine’s fragile sack of a body in my hand and swallowed it whole. The maggots writhed as they passed from my mouth into the warmth of my pharynx and thence to my larynx. I recalled that a friend from the BackPacker days had given me valuable information about such creatures.

Among the central Australian aboriginal tribes the so-called witchetty grub is valued as a foodstuff. The raw grub tastes like almonds and when lightly cooked the skin becomes crisp like roast chicken while the inside becomes light yellow, like a fried egg. The grub has a high protein content. I would be sustained by Celine’s murderers as I sought to avenge her.

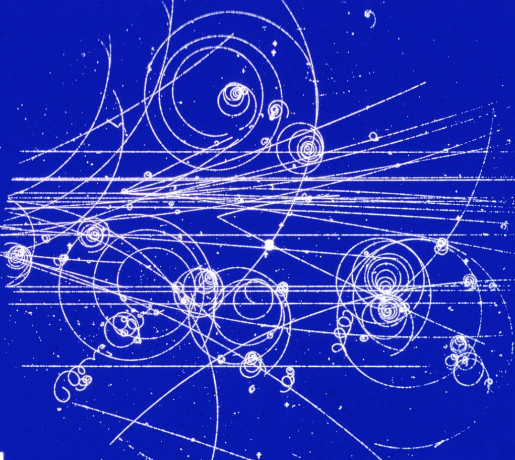

Little did I expect the dreadful contest that I had precipitated in my own stomach. As the grubs swelled and writhed, steadily consuming the lasagna upon which I had dined prior to my insectivorous digression, the body of the little songbird began to revive. I felt light flutterings against the lining of the warm pocket that until then I had seen only as the place where grub goes.

The stomach, however, is not designed to support life. The levels of hydrochloric acid necessary for digestion are capable of dissolving the bone of the beak and reducing the feathers to an uneven plastic sheath. I felt, however, that there was little that I could do. Then it occurred to me that I could tip the scales in favour of Celine by eating certain carefully chosen foods.

I went to a vegetarian restaurant near Warren Street tube station and ordered a sunflower seed bake. I found myself sharing a table with a young American competitive swimmer. She was in training for the London Olympics 2012. We talked about a range of non-swimming topics such as action painting, cheap reading glasses and the remarkable range of phobias routinely presented at the doctor’s surgery.

As we talked I became aware that, far from divorcing her profession from her predilections, everything she said reflected her experience at a deep level. She related to action painting because of her engagement with swimming free form, to reading glasses because of her absorption in submarine optics and phobias because her morbid fear of water gave her a rabid energy.

Celine reacted well to the sunflower seeds. She consumed them eagerly and, I suspect, began to peck at the maggots. I began to wonder what their reaction would be. Despite the predations of the songbird they were well adapted to the warm, moist environment. Was it possible that they would soon transform? If so, what form would they take?

When it came it took me completely by surprise. I had never imagined that the two sets of DNA were compatible. The lights were blinding but I was drawn to them. The dust from my arms rose in shimmering clouds. My voice was thick but fading fast. I shrugged and soared softly upwards. The dead skins of the transfigured maggots showered from my arsehole. Now I was the Mothman.

I soared over the land as we know it. It was really great, looking down and everything. Everyone wants to fly and I’m no exception. As I winged my way over Edinburgh I heard a piteous piping. I realised that the songbird Celine was still inside me, revitalised by her meal and keen to spread her wings. I opened my mouth and uncoiled my proboscis.

Fluttering, she twisted through my tubes and opened like an orchid in the air. Now we flew together. My own voice was a high-pitched twittering shriek but hers was a clear, high, pealing, cry. We soared over the military bases at Fairford, Feltwell, Greenham and Lakenheath. Celine’s revisioning of ‘The Power of Love’ brought the jets up. We could see the pilots in the windows.

“Wolfman engaged offensive! Two bandits right ten, one mile, low!” To my astonishment Celine suddenly spoke out: “Mothman, this is Mothman, visual, do not press!” “Bandit closing, committed.” “This is Mothman. Abort, Wolfman, bug out. I have super-powers and will deploy.” “Mothman, this is Wolfman, your legend precedes you. Aborting, aborting.”

In the early 80s it was found that young American fliers responded more precisely and obediently to a female rather than male voice transmitted from the control tower. It is conceivable that a reversion to a mother/son relationship is more readily effected in a hairline situation. The reluctant politeness of the everyday “Yes, Ma’am” is overridden by the submissive “I copy that”.

Celine, nestling on my back, had seduced the fliers with her siren song. As they arced away we swooped and soared, tonguing tiny flies, spinning in the light, drinking the rain, gazing down on the world remade. We had left shame and putrescence behind but we knew we would never land.